Part 1

It was 1980, and I was driving my beat-up car toward Sullivan County Community College in upstate New York. My name is Bobby, and I was just an anxious freshman trying to start a new chapter. I didn’t know a soul on campus. I wasn’t popular in high school, and honestly, I was terrified I wouldn’t make any friends.

I pulled into the parking lot, took a deep breath, and grabbed my bags. But as soon as I stepped onto the campus lawn, something bizarre happened.

People—total strangers—were waving at me.

“Hey! Good to have you back!” a guy shouted.

A girl ran up, hugged me, and kissed me on the cheek. “I missed you so much!” she beamed.

I froze. “I… I think you have the wrong person,” I stammered. “I don’t know you.”

She just laughed, slapped my arm playfully, and ran off.

I walked into the dorms, completely bewildered. Guys were high-fiving me in the hallway. Then, just as I turned toward my room, someone yelled out behind me.

“Yo, Eddie! What’s going on, man?”

I turned around. “I’m not Eddie,” I said, my voice shaking a little. “My name is Bobby. Who is Eddie?”

The guy looked at me like I was crazy. “Okay, Eddie. funny joke,” he said and walked away.

I got into my room and shut the door, my heart pounding. This wasn’t normal. This wasn’t how a first day of college was supposed to go. I sat on my bed, staring at the wall, just wanting the world to stop spinning.

Knock. Knock.

I groaned. “Who is it?”

I opened the door, and there stood a guy I’d never seen before. But the moment he saw me, the color drained from his face. His jaw literally dropped. He started shaking.

“Were you adopted?” he whispered.

“Yeah,” I said, confused.

“Is your birthday July 12th?”

“Yeah…”

He took a step back, looking like he’d seen a ghost. “My name is Michael. My best friend is a guy named Eddie Galland. He decided not to come back to school this year… and you are his clone.”

We ran to a payphone. My hands were trembling as Michael dialed the number. When a voice answered, I grabbed the receiver.

“Hello?” the voice said.

It was my voice. I was talking to myself.

“I think… I think I’m your brother,” I whispered.

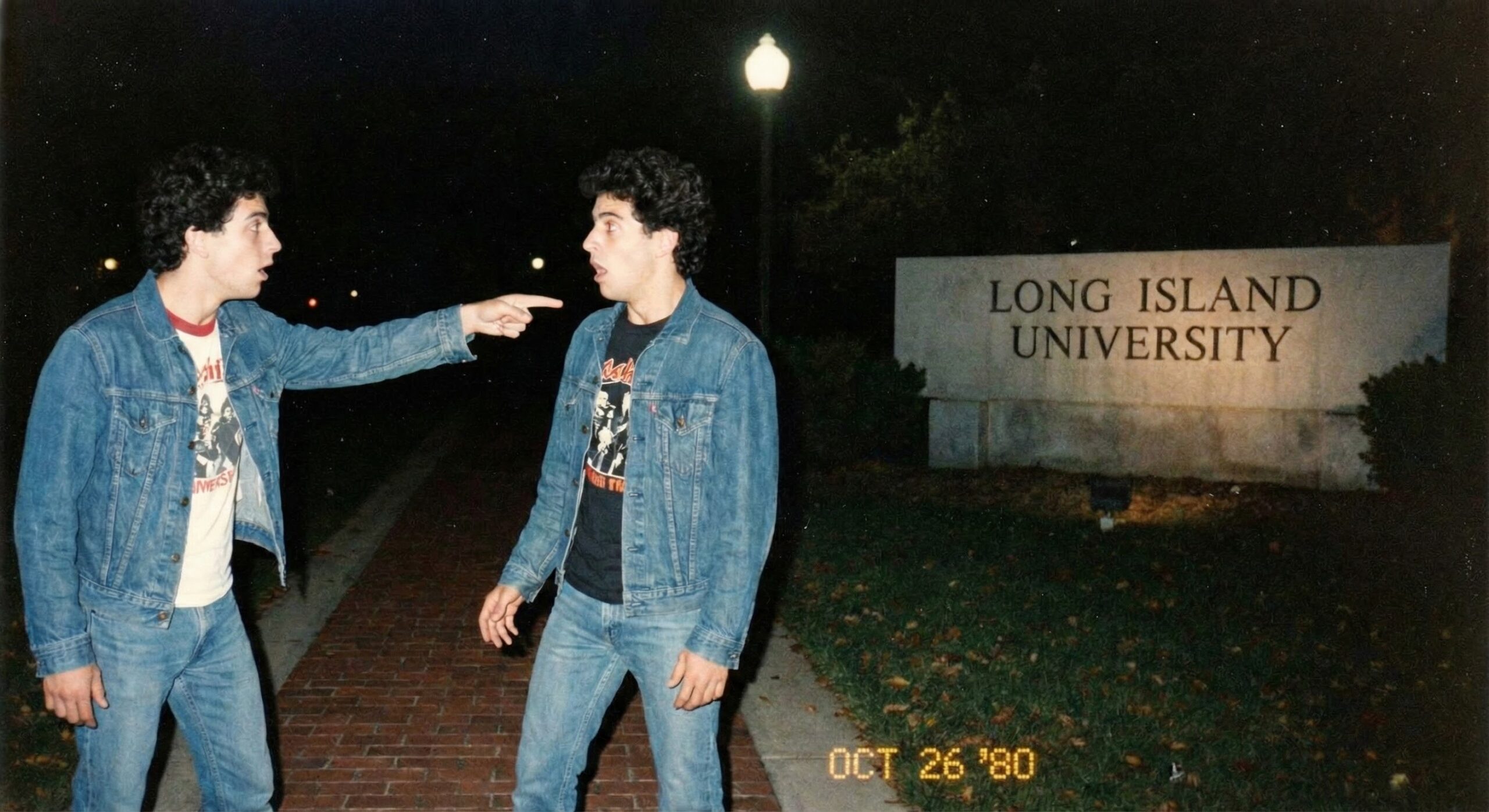

That night, Michael and I drove two hours to Long Island. It was pitch black when we pulled up to a house in a quiet suburb. It was the only house on the street with all the lights blazing.

I walked up the path, my legs feeling like lead. Before I could even knock, the door flew open.

And there I was.

Standing in the doorway was a boy who had my face, my eyes, my hands. We stared at each other for a full minute, frozen in shock. Then, we just burst out laughing. We hugged like we’d known each other for a thousand years.

But we didn’t know that our reunion was about to trigger a chain of events that would expose a horrifying secret… and eventually lead to a tragedy we could never come back from.

Because there wasn’t just two of us.

Part 2

The days following my reunion with Eddie were a blur of adrenaline and disbelief. It felt like the world had tilted on its axis. We were two nineteen-year-old kids who had just found the missing piece of a puzzle we didn’t even know we were solving. Newsday, the big local paper here on Long Island, caught wind of the story immediately. It was the kind of human-interest gold that journalists dream of: “Separated at Birth: The Twin Reunion.” They ran a huge spread, photos of us grinning like idiots, our identical hands held up for comparison.

We thought that was it. We thought we had reached the peak of the mountain. But we were wrong. We were just at the foothills.

A few days after the article ran, the phone rang at Eddie’s parents’ house. I was there, crashing in his room, trying to make up for nineteen years of lost time. Eddie’s mom, a sweet but increasingly overwhelmed woman, picked up the receiver. I watched her from the kitchen table. Her face went slack. She didn’t say a word for a long time, just listened. Then, the color drained out of her cheeks, and the phone slipped from her hand, clattering onto the linoleum floor.

“They’re coming out of the woodwork,” she whispered, staring into the middle distance.

The voice on the other end of the line had been a young man named David Kelman. He was a student at Queens College. He had been sitting in his dorm room when his friends burst in, waving the Newsday article in his face. “Dave, you gotta see this,” they’d said. “These guys… they aren’t just similar. They’re you.”

David had looked at the photo. He saw his own face staring back at him times two. He saw our hands—big, meaty hands, “catcher’s mitts” we called them—and looked at his own. Then he checked the birth date in the article: July 12, 1961. The hospital: Long Island Jewish.

David wasn’t just a lookalike. He was the third one. We weren’t twins. We were triplets.

Eddie and I didn’t wait. We got in my beat-up Volvo and tore down the Long Island Expressway toward Queens. My heart was hammering against my ribs so hard I thought it might crack them. Two was a miracle. Three? Three felt like divine intervention. Or magic. Or something else entirely that I couldn’t name yet.

We pulled up to David’s house in a quiet, working-class neighborhood. It was modest, squeezed in among rows of similar brick homes. We ran up the steps, and before we could even knock, the door swung open.

And there he was.

If seeing Eddie was like looking in a mirror, seeing David was like stepping into a hall of mirrors. The three of us stood there in the entryway, this tiny Queens foyer, just staring. The silence lasted maybe five seconds. Then, without a word, we collapsed into each other. It wasn’t a hug; it was a pile-on. We were wrestling, laughing, crying, slapping each other’s backs. It was a puppy pile, pure instinct. It was the most euphoric feeling I have ever experienced in my life. It was a physical sensation, like a magnetic snap. Click. We are whole.

We spent that first night sitting on David’s floor, smoking the same brand of Marlboro Reds, drinking beers, and just talking over each other. And that was the thing—we didn’t just look alike. We were alike. We sat the same way, legs crossed at the ankle. We used the same hand gestures. We liked the same older women. We had the same sense of humor. We finished each other’s sentences, literally. One of us would start a thought, and another would pick it up mid-stream, and the third would punchline it. It was like we shared a single brain split across three bodies.

Overnight, we went from anonymous college kids to the most famous people in New York City. The media couldn’t get enough of us. We were everywhere. The Phil Donahue Show, The Today Show, magazines, newspapers. We were the “miracle triplets.”

And god, we milked it. We were nineteen, twenty years old in New York City in the early 80s. The city was gritty, electric, and alive, and we owned it. We dropped out of college—who needs a degree when you’re a national phenomenon?—and got an apartment together in SoHo. It was a bachelor pad straight out of a movie. We threw parties that lasted for days. We walked into the most exclusive clubs—Studio 54, the Limelight—and the velvet ropes just parted for us. We met Madonna. We hung out with rock stars.

We wore matching outfits because we knew it drove the girls crazy. We played up the triplet thing hard. We were a unit. A brand. “The Boys.”

But while we were living the high life, drinking champagne and basking in the flashbulbs, our parents—our adoptive families—were starting to ask the questions we were too young and too distracted to ask.

It started with a nagging feeling in the back of my father’s mind. My dad was a doctor, a man of science, precise and logical. He couldn’t wrap his head around it. How does an adoption agency—specifically Louise Wise Services, the most prestigious Jewish adoption agency in New York, the agency for the wealthy and the elite—accidentally separate triplets?

“It doesn’t make sense, Bobby,” he told me one Sunday dinner. “You don’t just lose two siblings. They told us you were an only child. They lied.”

The three sets of parents decided to band together. They were an odd group. My parents were affluent, living in Scarsdale. Eddie’s parents were middle-class, a teacher and a housewife from the suburbs. David’s family was blue-collar, immigrant stock, hardworking people calling Queens home. Under normal circumstances, these three families probably never would have crossed paths. But now, they were bound by this incredible, infuriating mystery.

They demanded a meeting with Louise Wise Services.

I remember my dad telling me about that meeting later. He said the atmosphere in the room was cold, sterile. The agency executives sat behind a long mahogany table, looking down their noses at our parents. They were defensive.

“Why were they separated?” David’s aunt, who had helped raise him, asked, her voice trembling with anger. “Why did you keep them apart?”

The head of the agency, a stiff man in a grey suit, adjusted his glasses. “It was difficult to place three children together,” he said smoothly. “We felt it was in the best interest of the children to separate them to ensure they each found a good home.”

My father slammed his hand on the table. “That is absolute bullshit! If you had told me there were three of them, I would have taken all three! I would have taken them in a heartbeat!”

The other parents nodded in agreement. They were furious. They felt robbed. They had missed out on seeing their sons grow up together. They had been made complicit in a lie they didn’t know they were telling.

The agency wouldn’t budge. They hid behind “confidentiality” and “standard procedure.” They stoned-walled our families completely. Defeated and fuming, the parents got up to leave.

But then, something happened. A small moment that changed everything.

As they were walking down the hallway to the elevator, my dad realized he had left his umbrella in the conference room. He told the others to wait and walked back. The carpet was thick, muffling his footsteps. He reached the door to the conference room, which was slightly ajar.

He was about to push it open when he heard a sound that made him freeze.

Pop.

The sound of a cork. Then the clink of glasses. Laughter.

He peered through the crack in the door. The agency executives—the same people who had just told our parents they were “so sorry” and it was just “policy”—were pouring champagne. They were toasting. They looked relieved. celebratory, even.

“That was close,” he heard one of them say.

My dad didn’t go in. He turned around, his blood running cold, and walked back to the elevator. He was shaking. “They’re hiding something,” he told the other parents. “They aren’t sorry. They’re celebrating that we didn’t figure it out.”

That was the first crack in the façade. The first hint that our lives weren’t just a happy accident, but something darker. Something engineered.

Our parents tried to hire lawyers. They went to the best firms in Manhattan. Initially, the lawyers were eager. This was a high-profile case. It had “class action lawsuit” written all over it. But then, one by one, the firms would call back a week later and drop the case.

“Conflict of interest,” they’d say. Or, “We can’t take this on right now.”

It was terrifying. Louise Wise Services wasn’t just an adoption agency; it was an institution connected to the most powerful Jewish families and philanthropists in New York. They had tentacles everywhere. They were shutting us down before we could even start.

But honestly? At twenty-one, I didn’t care. Not really. I let my dad worry about the conspiracy theories. I had my brothers. We had opened a restaurant in SoHo called Triplets. It was a Romanian steakhouse—a nod to the fact that we discovered we all loved steak and garlic.

The first year was a gold rush. The place was packed every night. We were the main attraction. We’d walk around the tables, chatting up customers, taking photos. We made over a million dollars that first year. We were kids, drowning in cash and attention.

But you can’t build a life on a novelty act.

As the shine of the reunion started to wear off, the reality of who we were—and more importantly, how we were raised—began to bleed through. The “nature vs. nurture” debate wasn’t just a theory for us; it was a cage match in our living room.

We all had the same DNA. We had the same charm, the same smile, the same way of holding a cigarette. But our souls? Our souls had been shaped by three very different worlds.

I was the Scarsdale kid. My father was a doctor, my mother a lawyer. I was raised in a house where problems were solved with logic and discussion. I was confident, maybe a little entitled, but steady. I was the “responsible” one.

David was the Queens kid. His father was a shop owner, a big, lovable bear of a man who worked with his hands. David was street-smart, tough, and fiercely loyal. He had a grit to him that I admired.

And then there was Eddie.

Eddie was raised in a middle-class suburb, but his home life was… different. His father was a strict disciplinarian. A teacher who believed in order and control. Eddie told us stories about his dad that made David and me uncomfortable. He wasn’t physically abusive in the way you see in movies, but he was cold. Rigid. Eddie had grown up feeling like he could never do anything right.

Eddie was the most charismatic of us. He was the manic energy of the group. He was the one who wanted the party to never end. But he was also the most fragile. He had these mood swings that would come out of nowhere. One minute he’d be on top of the table singing, and the next he’d be in the corner, dark and brooding, convinced everyone hated him.

These differences started to rot the business from the inside out.

We started fighting about the restaurant. David and I wanted to modernize, maybe expand. Eddie wanted to keep it exactly the same, afraid that any change would break the magic spell. The fights got ugly. We weren’t just business partners; we were siblings who hadn’t learned how to fight growing up. We didn’t have those years of childhood squabbles to teach us boundaries. We went for the throat every time.

“You think you’re better than us because you grew up with a silver spoon in your mouth, Bobby?” David would yell, his Queens accent thickening.

“And you think you can run a business like a corner bodega?” I’d shoot back.

And Eddie… Eddie would just scream. He couldn’t handle the conflict. He needed us to be perfect. He needed the fairy tale to be real because, without it, he was just a kid who didn’t fit in his own skin.

“Stop it! Just stop it!” Eddie would shout, tears in his eyes. “We’re supposed to be brothers! We’re supposed to be together!”

The tension became unbearable. The restaurant started to suffer. The parties stopped being fun and started feeling desperate.

I remember the day I decided to leave. We were in the back office of Triplets. The air was thick with smoke and resentment. We were arguing about money—always money.

“I’m out,” I said, throwing my keys on the desk. “I can’t do this anymore. I love you guys, but I can’t work with you.”

David looked at me with a cold resignation. He knew it was coming. But Eddie looked like I had just stabbed him in the chest.

“You can’t leave,” Eddie whispered. “If you leave, there is no Triplets. There’s just… us.”

“I have to, Eddie,” I said. I walked out the back door and into the humid New York night. I thought I was saving myself. I thought I was making a mature business decision.

I didn’t realize I was pulling the pin on a grenade that was holding Eddie together.

With the trio broken, Eddie began to spiral. The restaurant closed not long after. I moved out of the city, tried to start a more normal life, maybe go back to school. David went back to his family in Queens.

But Eddie had nowhere to go. He had defined his entire existence by us. By the “Triplets.” Without that identity, all the dark thoughts he had kept at bay with the fame and the noise came rushing back. He became manic-depressive. He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

I would get calls from him at 3:00 AM. He would be crying, talking a mile a minute, making no sense.

“Bobby, they’re watching us,” he’d say. “The agency. They did this to us. They messed us up.”

“Eddie, get some sleep,” I’d say, tired and dismissive. “It’s over. We’re just guys now.”

“No, you don’t understand!” he’d scream. “We aren’t guys! We’re experiments! That’s why we’re like this! That’s why I’m like this!”

I didn’t listen. I thought it was just the illness talking. I didn’t know yet that Eddie was right. I didn’t know that while we were fighting over steak knives and profit margins, a journalist named Lawrence Wright was sitting in a library, blowing dust off a scientific journal that would explain everything.

We weren’t just separated. We were distributed. Like samples in a lab.

And while I was trying to distance myself from my brothers to save my own sanity, Eddie was sinking deeper into a darkness that had been prepared for him before he was even born. The climax of our story wasn’t the reunion. The reunion was just the setup. The climax was coming, and it was going to break our hearts.

I remember the last time I saw Eddie alive. He looked thin. His eyes—our eyes—were haunted. He grabbed my arm, his grip surprisingly strong.

“It’s not fair, Bobby,” he said. “It’s not fair that they got to play god with us.”

I pulled away. “Take your meds, Eddie. You’ll feel better.”

I walked away. I left him there.

Two weeks later, the phone rang. It was David.

“Bobby,” he said, and his voice sounded like it was coming from the bottom of a well. “It’s Eddie.”

The silence on the line was deafening. It was the sound of the fairy tale dying.

“He’s gone, Bobby.”

That was the moment the rising action stopped, and the crash began. The fun was over. The tragedy had arrived. And the mystery of why—why us, why this, why him—was about to consume the rest of our lives.

Part 3

The funeral was a blur of black umbrellas and whispered condolences, but I don’t remember much of what people said. I only remember the visual shock of it. Standing there next to David, looking down at the casket, was like looking into a mirror that had shattered. We were the same. We were always the same. And now, one of us was in a box, cold and still, while the other two were standing in the rain, breathing.

It wasn’t just that I had lost a brother. I felt like I had lost a limb. Actually, it was worse than that. It felt like I was attending my own funeral. People couldn’t look David and me in the eye. It was too unsettling. Seeing two living versions of the dead man was too much for them to process.

After Eddie’s death, the silence in my life was deafening. The media circus packed up and left. The “Miracle Triplets” weren’t a fun, feel-good story anymore. Suicide doesn’t sell newspapers—at least, not the kind of newspapers that want happy endings. We were yesterday’s news, left to pick up the pieces of a tragedy we didn’t understand.

David and I drifted apart for a while. It hurt too much to look at him because every time I saw his face, I saw Eddie. I saw the ghost of the brother we failed to save. I retreated into my own life, trying to bury the guilt. I kept thinking, If I hadn’t left the restaurant… If I had picked up the phone that one night…

But while we were drowning in grief, a journalist named Lawrence Wright was digging.

Lawrence wasn’t looking for us specifically. He was researching a book about twins and the mysteries of identity. He was combing through obscure medical journals, the kind of dry, academic texts that no one reads unless they have to. And in the archives of a university library, he found something that stopped him cold.

It was a study titled “The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child.”

It referenced a secret study conducted in the 1960s and 70s by a prominent psychiatrist named Dr. Peter Neubauer. The study involved separating identical twins and triplets at birth and placing them in different socioeconomic environments to track their development.

Lawrence contacted me about a year after Eddie died. When he told me what he found, I didn’t want to believe it. It sounded like science fiction. It sounded like something the Nazis would have done—medical experimentation on children without consent.

“Bobby,” Lawrence said, his voice serious. “I think you guys were the crown jewel of this study. You weren’t separated because no one would take you. You were separated on purpose.”

The rage that hit me then was different from the grief. Grief is heavy; it pulls you down. Rage is hot; it burns you up.

David and I met with Lawrence. We started piecing together the memories from our childhoods that we had always dismissed as normal but now looked sinister.

We all remembered the “visitors.”

When I was a kid, maybe once or twice a year, these people would come to my house. A man and a woman. They said they were from the adoption agency, just doing a “routine follow-up.” They would bring toys, puzzles, and blocks. They would film me playing. They would ask me strange questions. They would have me ride a bike, draw a picture, solve a maze.

I loved those visits because I got attention. I thought I was special.

“I had them too,” David said, his face pale. “They came to the store. They watched me interact with my dad.”

“And Eddie…” I choked on the name. “Eddie told me about them too.”

We realized then that for the first ten years of our lives, we were being watched. Documented. Analyzed.

We weren’t children to Louise Wise Services. We were lab rats.

The pieces of the puzzle started to click together, and the picture they formed was horrifying. Dr. Peter Neubauer, a giant in the field of child psychiatry, had orchestrated a god-complex experiment. He wanted to solve the ultimate debate: Nature vs. Nurture.

Does our DNA define us? or does our upbringing?

To answer this, he needed identical genetic sets. He needed clones. And he needed to control the environments they grew up in.

They placed me, Bobby, in the “upper-class” home. My dad was a doctor, we lived in Scarsdale, I had money, education, and resources. I was the control group for “Affluence.”

They placed David in the “working-class” home. His parents were immigrants, blue-collar, English wasn’t their first language. But they were warm, loving, “salt of the earth” people. He was the control group for “The Struggle.”

And then… there was Eddie.

They placed Eddie in the “middle-class” home. But it wasn’t just about money. It was about the father figure.

This was the part that broke me. Lawrence Wright discovered that the researchers had cataloged the parenting styles of our adoptive families before they gave us to them.

My father was busy but rational. David’s father was warm and affectionate.

Eddie’s father? The researchers noted he was “strict,” “rigid,” and emotionally distant. They knew this. And they deliberately placed the third triplet—the one with the same sensitive, slightly manic genetic makeup as David and me—into the home with the least emotional support.

They wanted to see what would happen.

They wanted to see if a sensitive child would break under a rigid father.

And he did.

Eddie didn’t just have bad luck. He was set up to fail. His mental health struggles, his feeling of isolation, his constant need for validation—it was all exacerbated by the environment they chose for him. They wound him up and watched him spin out of control, scribbling notes on their clipboards while he suffered.

We found out that the researchers published some initial findings in journals, hiding our identities. They noted that all three of us banged our heads against the bars of our cribs as babies.

Think about that. Three babies, miles apart, all banging their heads in distress.

The researchers called it “separation anxiety.” They knew we missed each other. They knew we felt the phantom limb of our brothers. And instead of reuniting us, they wrote it down as a fascinating data point.

“Subject A exhibits signs of distress. Subject B exhibits identical signs.”

They watched us cry for each other in the dark, and they did nothing.

The injustice of it made me want to burn the city down. I thought about Eddie’s funeral again. I thought about him crying on the phone to me at 3 AM, saying, “Bobby, something is wrong with me.”

There was nothing wrong with him. There was something wrong with them.

David and I decided we couldn’t let this slide. We couldn’t just mourn Eddie; we had to avenge him. We needed to find Dr. Neubauer. We needed to look him in the eye and ask him why.

But Dr. Neubauer was an old man by then, insulated by wealth and prestige. He refused to speak to us. He refused to apologize. To him, we weren’t human beings with souls. We were data. We were a successful experiment.

We learned that the study had been shut down in 1980—the same year we found each other. They panicked. They knew that if the public found out they had separated siblings for science, it would be a scandal. So they buried it. They sealed the records.

But the damage was done.

The “Climax” of a story is usually a moment of action. A fight scene. A chase. But for us, the climax was a realization. It was the moment the floor dropped out from under our universe.

We realized that our entire lives had been manipulated. Our parents—our adoptive parents—were victims too. They didn’t know. My dad went to his grave hating Louise Wise Services, but he never knew the full extent of the evil. He just thought they were incompetent. He didn’t know they were malevolent.

The guilt I felt about Eddie shifted. It wasn’t my fault I left the restaurant. It wasn’t David’s fault he fought with Eddie. We were three young men thrust into a pressure cooker that had been heating up since the day we were born. We were traumatized children masquerading as rock stars.

And Eddie… Eddie was the collateral damage of a scientist’s curiosity.

I remember sitting in my living room, looking at the Newsday article from 1980, the one with our smiling faces. We looked so happy. We looked like we had won the lottery.

But now, looking at that photo, all I could see was a tragedy in progress. I saw three boys who were desperate to find a connection they had been robbed of. We held onto each other so tight because deep down, our bodies remembered the trauma of being ripped apart.

And the worst part? We weren’t the only ones.

Lawrence Wright told us there were others. Other twins. Other triplets. A woman named Paula Bernstein found her identical twin, Elyse Schein. They were part of the same study. They had been separated too.

How many of us were there? How many people are walking around New York right now, feeling like something is missing, not knowing that their other half is living five miles away, being studied by the same ghost writers?

The scale of the betrayal was monumental. It wasn’t just a family secret. It was an institutional conspiracy involving the adoption agency, the psychiatrists, and the state of New York.

And the man responsible, Dr. Neubauer, died in 2008. He took his secrets to the grave. He never faced a judge. He never faced a jury. And worst of all, he never faced us.

We were left with the wreckage. David and I were the survivors of a shipwreck that no one else saw happen. And as we moved into middle age, the anger settled into a hard, cold resolve. We wanted the files. We wanted to see what they wrote about us. We wanted to know if they predicted Eddie’s death.

Did they write it down? “Subject C is showing signs of suicidal ideation.” Did they just file that away?

We had to know.

Part 4

The resolution of a story is supposed to bring closure. The hero defeats the villain, the mystery is solved, and everyone walks into the sunset. But in real life, especially in a story like ours, there is no sunset. There is just the long, hard light of day.

For years, David and I hit brick walls. We demanded the records from the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, which had absorbed the Louise Wise agency. They told us the records were sealed. They told us they were protected by doctor-patient confidentiality—which was a sick joke, considering we were the “patients” and we were giving consent.

They were protecting themselves. They were protecting the legacy of Dr. Neubauer.

They told us the study records were sealed at Yale University and wouldn’t be released until the year 2066.

I did the math. I would be 105 years old. David would be 105. Eddie… Eddie would have been 105.

They had sealed the records until they were certain we were all dead. They wanted to wait until the “lab rats” had expired so we couldn’t sue, couldn’t scream, couldn’t shame them. It was the final insult. Even in death, they wanted to control the narrative.

But the world changed. The internet happened. Documentaries became powerful tools for justice.

In 2018, a filmmaker named Tim Wardle approached us. He wanted to make a documentary about our lives. Three Identical Strangers.

At first, I was hesitant. I didn’t want to drag up the pain again. I didn’t want to be the “entertainment” for another audience. But David and I talked about it. We realized this was our only weapon. If we couldn’t get the files through the courts, we would get them through the court of public opinion. We would shame them into releasing the truth.

Making the documentary was grueling. We had to sit in chairs and relive the best days of our lives and the worst days. We had to watch old footage of Eddie, laughing and dancing, and know that he was already dying inside.

But the film did exactly what we hoped it would do. When it premiered at Sundance, people were horrified. Audiences gasped. People cried. The story went viral again, but this time, not as a “feel-good” triplet story. It went viral as a horror story.

The pressure on the Jewish Board became insurmountable. They couldn’t hide behind 2066 anymore. The public outcry forced their hand.

Finally, after nearly forty years of lies, they agreed to release our files to us.

I remember the day we got them. It wasn’t a triumphant moment. It was heavy. We received thousands of pages of heavily redacted documents. Black ink lines covered names, dates, and specific locations. But the observations were there.

We read the notes the researchers made about us when we were toddlers.

“Bobby is aggressive, dominant.”

“David is passive, seeking affection.”

“Eddie is fearful, unstable.”

They had analyzed us like insects under a microscope.

But the most chilling part wasn’t what was in the files; it was what wasn’t. There was no conclusion. There was no grand scientific breakthrough. Dr. Neubauer never published the study.

Why?

Some say it’s because the results were inconclusive. Nature and Nurture are so intertwined that you can’t separate them, even if you split triplets.

But I think it’s because the results were too ugly.

I think they realized that by separating us, they had damaged us. They realized that the “Nurture” they provided—the separation itself—was the trauma. They couldn’t publish a study that proved they had destroyed the lives of the children they were supposed to be studying. So they shelved it. They hid it. They let it gather dust while we lived the consequences.

The documentary won awards. It was shortlisted for an Oscar. David and I walked red carpets again, just like in 1980. But this time, there was a ghost walking between us. Every interview we did, every photo we took, there was a gap where Eddie should have been.

People always ask us, “Do you forgive them?”

Forgiveness is a tricky word. Can I forgive the parents who adopted us? Yes. They didn’t know. They loved us the best way they knew how.

Can I forgive the agency? No. I can’t.

You don’t forgive someone for stealing your life. You don’t forgive someone for playing God with children.

But I have to live. David has to live.

David and I are closer now than we’ve ever been. We’re old men now. The thick dark hair is grey. The “catcher’s mitt” hands are wrinkled. We live quiet lives. I play golf. David spends time with his grandkids. We talk on the phone almost every day.

We talk about the weather. We talk about politics. We talk about our kids.

We rarely talk about the study anymore. We’ve said everything there is to say.

But sometimes, I think about the parallel universe where Dr. Neubauer never existed.

In that universe, the three of us grew up in the same house. Maybe we drove our parents crazy. Maybe we fought over toys. Maybe we shared a bedroom with bunk beds.

In that universe, Eddie isn’t the “tragic third triplet.” He’s just my brother Ed. Maybe he’s a teacher like his dad, or a salesman. Maybe he has a wife and kids. Maybe he’s happy.

That’s the hardest part—mourning the life that was stolen.

The scientists wanted to know what makes us who we are. Is it our genes, or is it our environment?

After a lifetime of being the subject of that question, I think I have the answer. But it’s not what they wanted to hear.

Biology is powerful. We walked the same, talked the same, loved the same things. You can’t outrun your DNA.

But love? Connection? Family? That’s what keeps you alive.

They proved that by taking it away from us. They proved that when you sever the bond between human beings who are meant to be together, you create a wound that never heals.

So, here is the epilogue of the “Three Identical Strangers.”

We survived. Two of us, anyway. We beat the odds. We found each other despite the entire world trying to keep us apart. We exposed the truth despite the most powerful institutions trying to bury it.

And every time I see David, every time I look into his eyes—my eyes—I see a victory.

They tried to make us strangers. But in the end, we died as brothers.

And somewhere, I hope Eddie knows that. I hope he knows that we fought for him. I hope he knows that the world finally knows his name, not as a data point, but as a man who deserved better.

This is my story. It’s a story about a miracle, a tragedy, and a crime. But mostly, it’s a story about the unbreakable pull of blood.

If you have a sibling, call them today. If you have a family, hold them close. Because you never know what forces are out there trying to tear you apart. And trust me, the only thing that matters in the end is who is standing next to you when the rain starts to fall.

Read the full story? You just did. But the real story is in the archives at Yale, waiting for 2066. Maybe one of you will be around to read the final chapter.

Until then, I’m signing off.

-Bobby.

News

Taylor Swift Officially Becomes World’s Richest Female Musician, Surpassing Rihanna with $1.6 Billion Net Worth

New Era of Wealth: Taylor Swift Claims Title of World’s Richest Female Musician In a historic shift for the music…

Secretary Hegseth Issues Stunning Update on Wounded National Guard Hero & Vows Justice After DC Tragedy

WASHINGTON D.C. — In a moment that has gripped the nation with a mix of profound sorrow and steely resolve,…

Washington Blown Wide Open: Pete Hegseth Accuses Barack Obama of Secretly Engineering ‘Narrative’ in Capital Earthquake

WASHINGTON, D.C. — A political earthquake has struck the nation’s capital as Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth launched a blistering counter-offensive…

I Thought I Knew The Man I Married For 26 Years Until A Crying Woman Standing On My Front Porch In Illinois Handed Me A Suitcase And Said “He Promised You Would Take Care Of Us”

Part 1 I never believed silence could feel so heavy until the morning everything shattered. It was a Tuesday in…

From Shining Shoes in Texas to Owning the Tallest Building in Los Angeles: How a Janitor Defied the Laws of Segregation to Build a Banking Empire That Changed History Forever

Part 1: The Invisible Man My name is Bernard. People often ask me how a man born into the dust…

Homeless at 15 in New York: How I Turned My Trauma Into a Ticket to Harvard

Part 1 I smelled like the garbage bin I ate from. That is not a metaphor. It was my reality…

End of content

No more pages to load