Part 1

The Call That Changed Everything

The boardroom was a cathedral of glass and steel, designed to make the world look small. I sat at the head of a 12-foot walnut table, wearing a suit that cost more than my first car. I don’t raise my voice. I don’t need to. In this room, silence is the loudest weapon.

“Last look,” I said. “Nine digits. We don’t blink.”

Across from me, the visiting team shifted in their seats. A CFO tapped a pen nervously. The city of New York hummed beneath us—sirens and traffic, a world constantly sprinting.

My private phone vibrated.

I didn’t look down. No one calls that number during the day. I nodded to my lawyer. “Confirm. Own the deal.”

It vibrated again. I glanced down. Area code 503. Oregon.

I ignored it. Probably a wrong number. My thumb hovered over the silence button.

“Let’s be efficient,” I said. “Ten minutes to a handshake.”

The phone buzzed a third time, insistent, refusing to be ignored. I lifted a hand, stopping the meeting. My attorney froze. I stood up, took the phone, and stepped out onto the terrace.

The wind was cold, cutting through the warmth of the office. I answered without a greeting.

“Blackwell.”

“Mr. Robert Blackwell?” A woman’s voice. Calm, professional, but with a heavy undertone. “I’m calling from Columbia Memorial Hospital in Astoria, Oregon. You are listed as the emergency contact for a patient named Isa.”

For a second, the wind seemed to stop. The name Isa landed like a physical blow.

“That’s a mistake,” I said, trying to keep my voice steady. “We divorced eight months ago. Remove me from her file.”

On the other end, the nurse took a breath. “I understand, sir. But she was brought in in critical condition.”

I watched a crane swing a pane of glass on a neighboring tower. “You need to contact her attorney.”

“We don’t have an attorney listed,” the nurse said gently. “We have you.”

“That’s… an oversight.” I checked my watch. “Fix it.”

I was about to hang up. I wanted to go back inside, to the numbers, to the logic. But the phone vibrated against my ear.

“Mr. Blackwell,” the nurse said, her voice firm now. “Please. We need to update you on her status.”

I looked at my reflection in the glass door. “Make it quick.”

“She underwent an emergency pre-term delivery.”

I stopped breathing. Pre-term delivery. Pregnant.

My mind calculated the dates without my permission. Eight months since the divorce. Two months before that. The math arranged itself into a single, impossible image.

“Is there a supervising physician?” I asked, my voice sounding strange to my own ears.

“Dr. Rostova is with Isa. She’s stabilizing post-op, but her condition is complex. She is battling a severe autoimmune flare.” A pause. “Sir… she listed you for herself.”

I closed my eyes. Isa. The woman who left me because she said she needed “space.”

“And,” the nurse continued, her voice softening, “You are also listed as the emergency contact for the infant.”

The world tilted. The infant.

“What is his condition?” I asked, barely a whisper.

“Male. Very low birth weight. Currently in the NICU. The team is optimistic, but he is very small. It’s hour by hour.”

I looked back into the boardroom. The men in suits, the contracts, the millions of dollars on the table. It all looked like dust.

“We’ll need consent for treatment if her status changes,” the nurse said. “I realize you aren’t her husband anymore, but there is no one else. Just you, Mr. Blackwell. Just you.”

I imagined a form, a blank field, and my name written in Isa’s elegant hand. She had no family. She had cut ties with everyone. Except, apparently, me.

“Text me the address.” The decision was made before I even thought it.

“Sir,” the nurse said, relieved. “We’re in Astoria. It’s a two-hour drive from Portland if the weather holds. It’s storming on the coast.”

“I don’t care about the weather.”

I ended the call. I walked back into the boardroom. The air felt too hot, too fake.

My General Counsel stood up. “Timing on the filing?”

“Adjourned,” I said.

The chairwoman across from me frowned. “We finally rattled you, Blackwell?”

I picked up my pen and slid it into my pocket. “You’ll have your answer in 48 hours.”

“Robert,” my CFO said, panicked. “The market hates uncertainty.”

“So do I.”

I walked out. I took the elevator down, my heart pounding a rhythm I hadn’t felt in years. Outside, the winter air hit me. My car was waiting.

“Airport,” I told the driver. “Now.”

As we merged into traffic, I looked up at the steel tower I owned. I had built an empire, but I had missed the only thing that actually mattered.

And now, I was racing against a storm to meet a son I didn’t know I had.

Part 2

The sliding glass doors of Columbia Memorial Hospital hissed open, and the silence that greeted me was heavier than the storm I had just driven through. Outside, the Pacific wind was tearing at the coastline, a physical violence that I understood. Inside, the violence was different. It was hushed. It smelled of floor wax, rubbing alcohol, and the specific, metallic scent of anxiety.

I walked to the reception desk. My Italian leather shoes clicked against the linoleum, a sharp, authoritative sound that felt obscenely loud in a place designed for whispers.

“NICU,” I said again to the woman at the desk. I felt a strange detachment, as if I were watching myself from the security camera in the corner. I was Robert Blackwell, a man who moved markets with a nod. But here, I was just a man in a wet suit with a visitor’s badge that felt like a target on my chest.

“Second floor, West Wing,” she repeated, her eyes lingering on the water darkening the shoulders of my jacket. “Take the elevator to the left.”

The elevator ride was a slow ascent into a world I had not authorized. I checked my phone out of habit. No signal. The bars were grayed out, just like everything else in this town. For the first time in twenty years, I was offline. The merger, the board, the poison pill—they were dissolving into the ether.

When the doors opened, the air changed. It was warmer here, humidified for lungs that hadn’t finished growing.

A woman in blue scrubs was waiting. She looked tired in the way that mothers and soldiers look tired—a fatigue that had settled into her bones.

“Mr. Blackwell?”

“Yes.”

“I’m Joyce. I’m the charge nurse for the unit tonight.” She didn’t offer her hand; she knew better than to touch a man vibrating with this much tension. “Before we go in, I need you to scrub up. Sink is to your right. Up to the elbows. Two minutes.”

I obeyed. I stood at the stainless-steel sink, pumping antibacterial soap that smelled of fake lemons, and scrubbed. I watched the suds turn gray with the road grit and the invisible residue of New York City. I scrubbed until my skin was raw, as if I could wash away the eight months of silence between Isa and me.

“Okay,” Joyce said when I finished. “Follow me.”

The NICU was a dimly lit bay, humming with a sound that I can only describe as a collective, mechanical prayer. Beep. Hiss. Beep. Hiss. Rows of incubators glowed like bioluminescent creatures in a deep sea. There were nurses moving in the shadows, rocking chairs, adjusting tubes, their movements slow and reverent.

Joyce stopped at an incubator near the window. The storm outside was just a series of muffled thuds against the glass, powerless against this sanctuary.

“This is him,” she whispered.

I stepped forward.

The logic of my life—the spreadsheets, the risk assessments, the bottom lines—shattered.

He was impossibly small. That was my first thought. Not cute, not precious, but terrifyingly small. He looked like a secret that hadn’t been meant to be told yet. His skin was translucent, a roadmap of blue veins visible beneath the red flush. He was wearing a diaper the size of a playing card and a knit hat that looked enormous on his head.

Wires. There were so many wires. They taped to his chest, his foot, his navel. A tube ran into his mouth, taping his lips apart. His chest shuddered with a rhythm that wasn’t his own; a machine next to him sighed, forcing air into lungs that were still learning the concept of oxygen.

“We call him Baby Boy Blackwell,” Joyce said softly. “Until you give us a name.”

I gripped the metal rail of the incubator. My knuckles turned white. Baby Boy Blackwell.

“I didn’t know,” I whispered. The confession scraped my throat. “I didn’t know he existed.”

Joyce didn’t judge. In places like this, judgment is a luxury no one can afford. “He’s holding his own, Mr. Blackwell. He’s a fighter. 28 weeks. Two pounds, four ounces. But his heart rate is strong.”

I looked at the monitor. Green numbers. 145. 144. 146. A frantic, galloping pace.

“Can I…?” I didn’t know how to finish the sentence.

“You can touch him,” she said. “He knows your voice. He heard it in the womb. Hearing is one of the first senses to develop.”

He heard my voice. The thought was a knife. What had he heard in those last months before Isa left? He had heard silence. He had heard me on conference calls, negotiating hostile takeovers, dismantling companies. He had heard me tell his mother that I didn’t have time for dinner, that the gala was mandatory, that her fatigue was “psychosomatic.”

I reached through the circular port in the glass. The air inside was tropical, moist and hot. I extended my index finger, hovering it over his hand. His hand was the size of a grape.

Slowly, terrifyingly, I lowered my finger.

His skin felt tacky, fragile, like wet paper. And then, a reflex sparked. His tiny, translucent fingers curled around the tip of my finger. A grip. A claim.

The sensation traveled up my arm, bypassed my brain, and hit me in the center of my chest with the force of a train collision.

“He’s got you,” Joyce murmured.

I stared at the connection. My massive, manicured hand, which had signed billion-dollar checks, held captive by a creature who owned nothing but the breath in his lungs.

“He looks like her,” I said, my voice breaking. It was true. Even through the tubes, I saw the shape of Isa’s eyes, the stubborn set of a chin that shouldn’t exist yet.

“He does,” Joyce agreed. “Now, you need to see her.”

I pulled my finger away slowly. His hand drifted back to the mattress, empty. The loss felt immediate.

“Dr. Rostova is waiting in the consultation room,” Joyce said. “And then I’ll take you to Room 204.”

I nodded, stepping back into the corridor. The transition from the warm, blue-lit womb of the NICU to the harsh fluorescent lights of the hallway made me squint.

The consultation room was stark. A table, three chairs, a box of tissues that looked like an admission of defeat. Dr. Eva Rostova was standing by the window, looking out at the rain. She turned when I entered. She was a woman cut from iron and exhaustion, her graying hair pulled back in a severe bun. She wore a white coat that had seen too many nights like this one.

She didn’t offer a handshake. She pointed to a chair. “Sit, Mr. Blackwell.”

I sat. I didn’t lean back. I stayed on the edge, ready to bolt or fight. “Tell me.”

She opened a file on the table. It was thick. Too thick for a sudden emergency.

“Isa is in critical condition,” Rostova began, her accent faint, Eastern European, precise. “She hemorrhaged during the emergency C-section. We managed to stop the bleeding, but her body was already at a breaking point before the surgery began.”

“Breaking point? Why?”

Rostova looked at me over the rim of her glasses. “She has Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. SLE. Are you aware of this diagnosis?”

“Lupus?” I frowned. “No. She was healthy. Tired, maybe. Anemic sometimes. But healthy.”

“She was not healthy, Mr. Blackwell. She has been managing aggressive autoimmune activity for at least a year. Likely longer.” Rostova tapped the file. “The pregnancy acted as a catalyst. It’s like pouring gasoline on a fire. Her kidneys are currently operating at less than fifteen percent capacity. Her platelets are dangerously low. Her body is attacking itself.”

I stared at the table. A year.

“We were married a year ago,” I said slowly. “We were together.”

“And she didn’t tell you?”

“No.”

Rostova sighed, a sound of frustration, not with me, but with the tragic predictability of human nature. “She presented to the clinic here in Astoria six months ago. She was already high-risk. I advised her that carrying to term could be fatal. She refused to terminate. She refused to contact you.”

“Why?” The word was a roar in my head, but it came out as a whisper. “I have the best specialists in the world on speed dial. I could have flown her to Mayo, to Hopkins. Why hide in a fishing town in Oregon?”

“Because,” Rostova said, closing the file with a snap. “She told me that stress was her trigger. And she told me that you were the stress.”

The room went silent. The hum of the ventilation system seemed to stop.

You were the stress.

I remembered the nights I came home at 2 AM, buzzing with the adrenaline of a deal, turning on the lights, pacing the bedroom, talking at her while she lay under the covers. I remembered the way I critiqued the dinner menu, the way I managed our vacations like military operations. I remembered her asking, once, quietly, “Robert, can we just stop? Can we just sit?”

And I had laughed. “Stopping is ding, Isa. Sharks drown if they stop.”*

“She left to save the baby,” Rostova said, her voice softer now, cutting through my memory. “And, in her own logic, to save you from watching her fail. Lupus is ugly, Mr. Blackwell. It is swelling, and rash, and pain, and failure of the organs. It is not the life she wanted for a man who values… perfection.”

She didn’t say the last word with malice, but it hit its mark.

“Can you save her?” I asked. I needed a transaction. I needed a deliverable.

“I don’t know,” Rostova said honestly. “We are blasting her with high-dose steroids and immunosuppressants. We are trying to buy her kidneys time to recover. But she is weak. She lost a lot of blood. The next 24 hours are the deciding factor.”

She stood up. “Come. She is in the ICU.”

Room 204 was at the end of the hall. It was a glass-walled room, isolated.

I walked in.

The woman in the bed was not the woman I had divorced.

Isa had been vibrant, a creature of silk and perfume, with hair that caught the light and a laugh that could disarm a room. The woman in the bed was a ghost.

Her face was swollen—the “moon face” of steroids, I would learn later. A rash, shaped like a butterfly, spanned her nose and cheeks, angry and red against her pale skin. Her hair was matted. A ventilator tube was taped to her mouth, forcing her chest to rise and fall in the same mechanical rhythm as our son’s down the hall.

There were bags of fluid hanging above her like strange fruit. Clear liquids, yellow liquids, blood.

I walked to the side of the bed. I didn’t know where to touch her. Her arms were bruised purple from IV lines. Her hands were swollen.

I grabbed a plastic chair and dragged it close to the bed. The screech of the legs against the floor made a nurse look up from the corner, but she didn’t say anything.

I sat down. I looked at her face.

“Isa,” I said.

The ventilator hissed. Chhh-kuhhh.

“I’m here.”

I waited for her eyes to flutter. For a hand to squeeze mine. Nothing. Just the machine.

“You’re a liar,” I told her, my voice trembling. “You stood in my office eight months ago. You looked me in the eye. You told me you were bored. You told me I was ‘too much and not enough.’ You told me you wanted to paint in a place where the light was gray.”

I leaned forward, resting my forehead against the metal rail of the bed.

“You didn’t tell me you were dying. You didn’t tell me you were pregnant.”

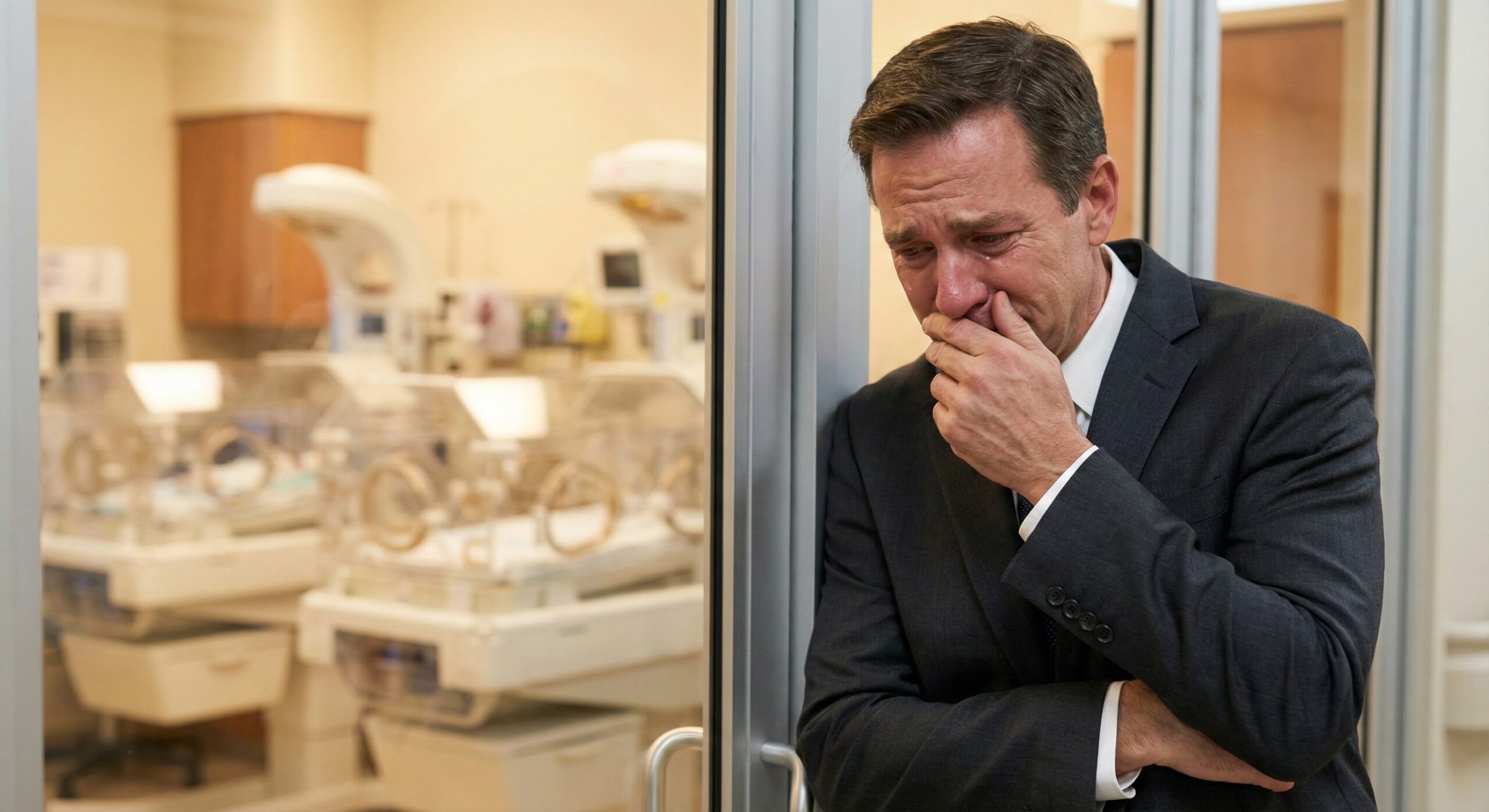

I realized I was crying. Not the polite, single-tear crying of movies. ugly, heaving sobs that hurt my ribs. I buried my face in my hands, smelling the soap from the NICU scrub, and let the facade of Robert Blackwell dismantle itself.

I sat there for an hour. Maybe two. Time moved differently here. It was measured in fluid drips and heartbeats.

Eventually, the nurse in the corner approached. “Mr. Blackwell?”

I looked up. My eyes felt gritty.

“Here,” she said. She handed me a large, manila envelope and a ring of keys. “These were in her personal effects. We usually lock them up, but Dr. Rostova said you might need them.”

I took the envelope. It was heavy.

“And,” the nurse added, checking her watch. “The cafeteria is closed, but there’s a vending machine down the hall. You should drink water.”

“I’m not thirsty.”

“Drink anyway. You’re no good to them if you pass out.”

She walked away.

I sat with the envelope on my lap. I felt like an intruder. Isa had curated her exit from my life with surgical precision. She had signed the NDA. She had refused alimony. She had vanished. Opening this felt like breaking the contract.

I opened it.

Inside was her wallet. Her phone (dead). A few loose receipts. And a small, leather-bound notebook. Moleskine. Black.

I knew this notebook. She used to sketch in it during breakfast while I read the Wall Street Journal.

I opened it.

The first half was sketches. Architectural details of New York. Faces on the subway. And then, the sketches stopped. The pages turned to lists.

Dr. Evans – 3 PM.

Creatinine levels: 2.4. Rising.

Proteinuria. High.

Don’t forget prenatal vitamins.

Sell the Cartier bracelet – need cash for rent.

I stared at the line. Sell the Cartier bracelet. I had given her that bracelet for our first anniversary. It cost $45,000. She had sold it to pay rent in Astoria?

I turned the page.

Date: November 12th.

He moved today. I felt him kick. It felt like a butterfly trapped in a jar. I wanted to call Robert. I dialed the number. I listened to his voicemail greeting. “You have reached the office of Robert Blackwell. Leave a message.”

I hung up. If I tell him, he will fix it. He will send a helicopter. He will hire a team of doctors. He will put me in a penthouse and watch me with those hawk eyes, checking for weakness. I can’t be his project. I can’t be a failing asset. I have to do this alone. If I lose the baby, I lose it alone. If I de, I de alone. He can’t handle grief. He turns it into anger. I won’t let him hate me.

I slammed the book shut. The words burned.

He turns it into anger.

Was she wrong? What was I feeling right now? I was furious. I was enraged that she had stolen this from me—the pregnancy, the fear, the chance to help. But beneath the anger, she was right. I was terrified of grief. I had built a fortress of money to keep grief out.

I stood up. The room was too small. The sound of the ventilator was too loud.

I looked at the keys in my hand. A simple silver key ring with a plastic tag. 1422 Harbor St, Apt B.

I needed to see it. I needed to see the life she had chosen over me.

“I’ll be back,” I told the unconscious woman. “Don’t you dare leave while I’m gone.”

I walked out to the nurses’ station. “I’m stepping out for an hour. Call me if anything—anything—changes.”

“We have your number,” Joyce said.

I ran through the rain to my rental car. The storm had settled into a steady, drenching downpour. I drove through the empty streets of Astoria. It was a town of hills and Victorian houses that looked like they were clinging to the earth for dear life.

1422 Harbor Street was a narrow, weathered building above a used bookstore. The paint was peeling. The stairs leading up to Apartment B were external, wooden, and slick with rain.

I climbed them. My suit was soaked. I unlocked the door and pushed it open.

The smell hit me first. Lavender and turpentine. It was the smell of Isa.

I flipped the switch. A single bulb illuminated the room.

It was a studio apartment. You could fit the whole place inside the walk-in closet of our Manhattan penthouse.

There was a single bed pushed against the wall, covered in a quilt I didn’t recognize. A small kitchenette with a dripping faucet. A radiator that hissed.

But it was… peaceful.

There were paintings everywhere. Canvases stacked against the walls, drying on the easel, propped on chairs. They weren’t the polite, abstract watercolors she used to paint in New York. These were dark, moody oils. Stormy seas. Gray skies. Jagged cliffs. They were violent and beautiful.

I walked to the easel. There was a painting of a man.

It was me.

But it wasn’t the CEO. It was me asleep. My face was soft, unguarded. It was a version of me I barely recognized—the man I was in the minutes before the alarm went off.

I looked around the room. On the small table by the window, there was a stack of books. What to Expect When You’re Expecting. Living with Lupus. The Bible.

And a nursery corner.

She had cleared a space near the radiator. There was a second-hand crib, painted white. A mobile made of driftwood and sea glass hanging above it. A stack of diapers.

I walked to the crib. Inside, there was a stuffed bear. It was missing an eye. It looked used, loved.

I picked up the bear. I sat down on the edge of her bed. The mattress sagged.

This was where she had lived for eight months. While I was dining at Le Bernardin, she was here, painting me sleeping, timing her contractions, measuring her failing kidney function, and knitting a hat for a baby she might not live to meet.

She hadn’t left me for another man. She hadn’t left me for a “better” life. She had left me for this. For the freedom to be broken without disappointed audience.

I looked at the bedside table. There was a pill organizer, full of colorful tablets. And a piece of paper taped to the wall.

It was a list of names.

Robert Jr. (No, too heavy)

William

Gabriel

Eli (God is Salvation)

The name Eli was circled three times.

Eli.

I closed my eyes, clutching the one-eyed bear.

My phone buzzed in my pocket. I jumped, my heart hammering.

It was the hospital.

I answered before the first ring finished. “Blackwell.”

“Mr. Blackwell?” It was Dr. Rostova. Her voice was tight. “You need to come back. Now.”

“Is she…?”

“She’s crashing. Her blood pressure is bottoming out. We’re taking her back to surgery to try and relieve the pressure on her kidneys. Robert…”

She used my first name.

“You need to hurry.”

I dropped the phone. I didn’t bother to pick it up. I didn’t bother to lock the door of the apartment. I ran. I ran down the wooden stairs, slipping, catching myself on the railing, tearing my suit jacket. I didn’t care.

I drove like a madman back to the hospital, the wipers useless against the deluge.

Don’t you dare, I screamed in the silence of the car. Don’t you dare die on me now that I know.

I skidded into the parking lot. I ran through the automatic doors, past the startled receptionist, and sprinted down the hallway to the elevators. I didn’t wait. I took the stairs, taking them two at a time, my lungs burning.

When I burst onto the second floor, the quiet was gone.

Alarms were blaring. A Code Blue light was flashing above Room 204. A crash cart was being wheeled in. Nurses were running.

I saw Joyce. She stepped in front of me, blocking my path.

“You can’t go in there!” she shouted over the noise.

“That’s my wife!” I yelled back, forgetting the divorce, forgetting the paperwork. “That’s my wife!”

“They are working on her. You have to let them work!”

Through the glass, I saw them. Dr. Rostova was over Isa’s body. She was doing chest compressions.

One. Two. Three.

Isa’s body jerked with each compression. She looked like a ragdoll. The monitor was a flat, high-pitched whine.

Beeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeep.

“Charge to 200!” Rostova shouted.

“Clear!”

Use body jumped.

I slumped against the glass wall, sliding down until I hit the floor. I watched the scene unfold like a silent horror movie. I pressed my hands against the glass, spreading my fingers.

I bought the poison pill, I thought wildly. I fixed the merger. I fixed the stock price. Why can’t I fix this?

“Come on, Isa,” I whispered into the linoleum. “Come on.”

Rostova was sweating. She looked up at the monitor. Nothing.

“Again!” she barked. “Charge to 300!”

“Clear!”

Thump.

A pause. A terrifying, eternal second where the universe held its breath.

And then…

Beep.

Beep… beep.

A rhythm. Ragged, weak, but there.

Rostova slumped over the bed. She looked at the glass wall. She saw me sitting on the floor. She gave me a single, grim nod.

Joyce crouched down beside me. She put a hand on my shoulder.

“They got her back,” she said gently. “She’s still here.”

I put my head between my knees and tried to remember how to breathe. I was Robert Blackwell. I was worth three billion dollars. And I was the poorest man on earth, begging for a single heartbeat.

“Get me a chair,” I told Joyce, my voice hollow. “I’m not leaving this hallway.”

“Mr. Blackwell, you need to…”

“I said, get me a chair.”

She looked at me, saw the ruin in my eyes, and nodded. “Okay. I’ll get you a chair.”

I sat there as the dawn began to break over Astoria. The storm had passed, leaving the sky a bruised purple. I sat in the hallway between Room 204 and the NICU, the guardian of the two fragile heartbeats that now constituted my entire world.

I held the one-eyed bear from her apartment in my lap.

And for the first time in my life, I didn’t make a plan. I just waited.

Part 3

The hallway chair became my office, my bed, and my confessional. It was made of hard, blue plastic, the kind designed to be uncomfortable so you wouldn’t linger, but I lingered. I stayed there for forty-eight hours.

My suit, a charcoal bespoke piece from Milan, was ruined. It was wrinkled, stained with rain and the sweat of panic, and the cuff was torn from my sprint up the stairs. I didn’t care. In my previous life—the life that ended when I picked up that phone in the boardroom—I would have fired an assistant for a coffee stain on a lapel. Now, looking at my reflection in the darkened window of the nursery, I saw a man who looked like he had survived a shipwreck. And in every way that mattered, I had.

Dr. Rostova came and went. She was a woman of few words, which I appreciated. False hope is a cruelty I never tolerated in business, and I didn’t want it here.

“Kidneys are stagnant,” she said on the morning of the second day. “We are starting dialysis. A catheter in the neck. It is ugly, but necessary.”

“Do it,” I said.

“She is drifting in and out,” she added. “She asks for the baby. She does not ask for you.”

That hurt more than the sleeplessness. “Does she know I’m here?”

“I told her. She closes her eyes when I say your name.”

I nodded, swallowing the bitterness. I deserved that. I had spent a marriage making her feel small, and now she was making herself invisible to protect me. It was a twisted kind of logic, but it was the logic I had taught her: Weakness is a liability. Hide the liabilities.

I spent the hours between ICU updates in the NICU.

It was a different world in there. The NICU didn’t care about the stock market. It didn’t care about the weather. It cared about grams and milliliters.

I learned the language. Desats. Bradys. CPAP. Kangaroo Care.

Joyce, the nurse who had first greeted me, became my guide. She was tough, maternal, and unimpressed by my net worth.

“Wash your hands,” she’d bark when I walked in. “Thirty seconds. Don’t cheat.”

I stood over Eli’s incubator for hours. He was so still, except for the heave of his chest. His skin was getting less translucent, turning a pinkish-red that Joyce said was good.

“He needs to know you’re here,” Joyce said on the third afternoon. “Talk to him. Read to him. The sound of a male voice is lower frequency; it soothes them differently than ours.”

I felt foolish. I was a man who gave keynote speeches at Davos. I negotiated with heads of state. But speaking to a two-pound human through a piece of plastic terrified me.

I pulled out my phone. I had no children’s books. I had no fairy tales. I opened the only app that had text. The Wall Street Journal.

“Okay, Eli,” I whispered, leaning close to the porthole. “Let’s look at the futures market.”

I read him an article about the volatility of oil prices. I read him an op-ed about interest rates. My voice was a low rumble in the quiet room.

“The market correction is inevitable,” I read softly. “But resilience is the key indicator of long-term value.”

I stopped. I looked at his tiny, clenched fist.

“That’s you, kid,” I whispered. “Resilience. You’re the long-term value.”

The monitor chirped. His heart rate, which had been fluctuating, settled into a steady rhythm.

“He likes economics,” Joyce said, walking by with a smile. “Or maybe he just likes knowing his dad is boring him to sleep.”

Dad.

The word settled on my shoulders like a heavy, warm coat.

The crisis point came on the fourth night.

I was dozing in the hallway chair, my head tipped back against the wall, when my phone buzzed. It wasn’t the hospital. It was New York.

My General Counsel.

I stared at the screen. It was 3:00 AM in New York. If he was calling, the building was burning down.

I answered. “Blackwell.”

“Robert,” his voice was tight. “Where the hell are you? The board is convening in six hours. The poison pill triggered, but without your signature on the counter-filing, the hostile bid goes through. We lose majority control. We lose the company, Robert.”

I rubbed my eyes. The hallway was dim. I could hear the rhythmic whoosh of the ventilator from Isa’s room.

“Let them have it,” I said.

Silence. Absolute, stunned silence.

“I’m sorry, the connection must be bad,” he stammered. “Did you say… let them have it?”

“I said, let them have it. Sell my shares. Cash me out. Or don’t. I don’t care.”

“Robert, are you drunk? Are you having a breakdown? We are talking about an empire. Your grandfather built this foundation. You spent twenty years expanding it. You’re going to walk away?”

I looked through the glass of Room 204. I saw the silhouette of the dialysis machine, cleaning the blood of the woman I loved because her own body was too tired to do it. I thought about the crib in the apartment above the bookstore. I thought about the list of names taped to the wall. God is Salvation.

“I’m not walking away, David,” I said quietly. “I’m walking toward something else.”

“This is suicide,” he hissed. “Professional suicide. You’ll be a pariah.”

“Then I’ll be a pariah.”

“Robert, listen to me—”

“No, you listen. Do not call this number again unless it is to tell me the wire transfer is complete. I am no longer the CEO. I am a father. And right now, I’m busy.”

I hung up. Then, I powered the phone off.

It felt like cutting an anchor chain. I was adrift, but for the first time, I wasn’t sinking.

Isa woke up properly the next morning.

The sun was trying to break through the coastal fog, casting a pale, milky light into the room. I was sitting by the bed, reading the Moleskine journal again, trying to memorize the parts of her mind I had neglected.

Her breathing changed. The rhythm hitched.

I looked up. Her eyes were open. They were glassy, unfocused, but they found me.

Panic flared in them instantly. She tried to move, but her hands were restrained by IV lines.

“Robert?” Her voice was a ruin. A dry croak around the tube.

I stood up, dropping the book. “I’m here. Don’t try to talk. You’re okay.”

She shook her head, a frantic, tiny movement. Tears welled in her eyes and spilled over, tracking through the butterfly rash on her cheeks. She looked ashamed.

That broke me. She was lying in a hospital bed, her body failing her, and she was ashamed that I was seeing it.

“Shh,” I soothed, reaching out to brush the hair from her forehead. Her skin was hot. “It’s okay.”

She pulled her face away from my hand. She pointed a trembling finger at the door. Go.

“No,” I said firmly. “I’m not going.”

She tried to speak again. The nurse, sensing the agitation, came in to check the alarms. “Mr. Blackwell, if she gets too upset, her blood pressure will spike. You might need to step out.”

“I’m not stepping out,” I said, my voice dropping to that boardroom tone, the one that brokered treaties. “She needs to know I know.”

I looked at Isa. I held up the Moleskine notebook.

Her eyes went wide. The shame deepened into horror.

“I read it,” I said softly. “I know about the diagnosis. I know about the apartment. I know about the bracelet you sold.”

She closed her eyes, defeated.

“Isa, look at me.”

She wouldn’t.

I sat on the edge of the bed, ignoring the nurse’s warning look. I leaned close to her ear.

“You wrote that you left because you didn’t want to be a ‘failing asset.’ You wrote that I would hate you for being sick.”

I took her hand. It was swollen, puffy with fluid. I squeezed it gently.

“You were right about a lot of things, Isa. You were right that I was cold. You were right that I was obsessed with control. But you were wrong about this. I don’t hate you. I hate myself for making you feel like you had to do this alone.”

She opened her eyes. They were searching mine, looking for the lie. Looking for the pity.

“I saw Eli,” I said.

The name hit her like a drug. Her face softened.

“He’s beautiful,” I said, choking up. “He’s small, and he’s angry, and he has your chin. I read him the Wall Street Journal. He fell asleep.”

A ghost of a smile touched her lips. It was painful to watch, but it was there.

“I’m staying,” I told her. “I sold the shares. I quit the board. I’m not the CEO anymore. I’m just… I’m just Robert. And I’m the emergency contact. You’re stuck with me.”

She looked at me for a long time. The machines beeped. The rain tapped against the glass. Finally, she turned her hand over in mine and squeezed back.

It was weak, barely a flutter, but it was enough.

Recovery was not a montage. It was a grind.

Isa didn’t just “get better.” She survived. Her kidneys were stubborn. We spent three weeks in that hospital. Three weeks of dialysis. Three weeks of watching her relearn how to walk to the bathroom without fainting.

I became a nurse. Me, Robert Blackwell, who had never washed his own dishes. I learned how to empty bedpans. I learned how to sponge-bathe her feverish skin. I learned how to rub ice chips on her cracked lips.

There was no dignity in it, and that was the point. We found intimacy in the lack of dignity. We stripped away the layers of pretense we had built our marriage on. There were no tuxedos, no gala dresses, no witty banter. There was just the raw mechanics of staying alive.

And there was Eli.

Every day, he grew. Joyce let me hold him for the first time on day ten.

“Shirt off,” she commanded.

“Excuse me?”

“Skin to skin. Kangaroo care. It regulates his heart rate and temperature. He needs to feel your heartbeat.”

I unbuttoned my shirt. I sat in the rocking chair. Joyce lifted the tiny tangle of wires and baby out of the incubator and placed him on my bare chest.

He was weightless. He was heat.

He settled against me, his ear over my heart. He let out a small sigh, a puff of air against my skin.

I stopped breathing. I was afraid the rise and fall of my own chest would disturb him.

“Relax,” Joyce whispered. “You’re tense. He feels that.”

I closed my eyes. I thought about the ocean outside. I thought about the painting in Isa’s apartment. Me, sleeping.

I exhaled. My shoulders dropped.

Eli wiggled, digging his tiny nose into my pectoral muscle, and went still.

In that moment, holding a two-pound boy in a dark room in Oregon, I felt a shift in the universe. I realized that every dollar I had ever made was just paper. This—this heat, this breath—was the only currency that had ever mattered.

I sat there for two hours until my arms were numb. I would have sat there for a hundred years.

But the climax wasn’t over. The universe likes to test your resolve one last time.

It was three weeks in. Isa was off the ventilator, sitting up, eating solid food. We were talking about discharge. We were talking about the future.

And then the Code Blue alarm went off. But it wasn’t for Room 204.

It was for the NICU.

I was in Isa’s room helping her drink tea. The alarm blared—a specific, piercing sequence.

Code Blue, NICU. Code Blue, NICU.

Isa dropped the cup. It shattered on the floor.

“Robert,” she gasped, her eyes going wide with terror. “Go.”

I didn’t wait. I ran.

The hallway to the NICU seemed to stretch for miles. I burst through the doors.

The unit was chaotic. Nurses were swarming around one incubator.

Eli’s.

Joyce was there. A doctor I hadn’t met was there. They were working on him.

“He’s bradying down!” someone shouted. “Heart rate is 60. 50.”

“Bag him! Give me the ambu-bag!”

I slammed into the glass wall of the unit, my hands pressing against it. I saw my son turning blue. A deep, terrifying gray-blue. He looked like a doll that had been discarded.

Joyce was using a small bag to pump air into his lungs. Her face was grim.

“Come on, little man,” she was chanting. “Come on, breathe.”

I watched them work on my son. I watched them perform CPR on a chest the size of a lemon. Two fingers. Press. Press. Press.

I couldn’t breathe. I felt my knees give out. I slid down the wall, clutching my chest.

This is the price, I thought. This is the price for the years of neglect. The universe gave him to me, and now it’s taking him back because I don’t deserve him.

“Please,” I whispered. I didn’t believe in God. I believed in markets. But in that moment, I prayed to everything. To the storm, to the ocean, to the lights. “Take me. Take the money. Take the other kidney. Just let him breathe.”

Minutes passed. Years passed.

And then, a sound.

A thin, high-pitched wail. It sounded like a kitten.

“He’s back,” the doctor said, exhaling. “Sats are coming up. Color is returning.”

Joyce looked up. She saw me on the floor outside. She walked over and opened the door.

She looked shaken. “He had an apnea spell. A bad one. He forgot to breathe. It happens with preemies. But he’s back.”

I couldn’t stand up. I crawled—literally crawled—to the side of the incubator.

He was pink again. He was crying. It was the most beautiful sound I had ever heard. It was the sound of fight.

I reached through the port and put my hand on his head.

“You’re grounded,” I sobbed, laughing and crying at the same time. “You are grounded until you are thirty.”

That night, I didn’t leave the NICU. I slept on the floor beside his incubator. And every time the monitor beeped, I woke up, checked his chest, and whispered, “Breathe.”

We both learned how to breathe that night.

Part 4

Discharge day came on a Tuesday. It was anti-climactic, which is exactly what we wanted. There were no paparazzi. No black SUVs. Just a rusted Toyota Camry I had rented from a local lot because the luxury rental felt obscene.

Isa was in a wheelchair. She was thin, frail, but her eyes were clear. She held a bundle of blankets that contained Eli. He was five pounds now. A heavyweight champion.

I pushed the wheelchair. We walked out of the sliding doors into the parking lot.

The sun was blinding. After a month of hospital fluorescent, natural light felt aggressive. The air smelled of low tide and pine needles.

“It smells like the world,” Isa whispered, closing her eyes and inhaling.

I helped her into the car. I strapped the car seat in with the intensity of a bomb disposal technician. I checked the straps four times.

“Robert,” Isa said gently. “He’s secure.”

“I know.” I checked it a fifth time.

We drove to the apartment. I had kept the rental on Harbor Street, but I had also rented the small house next door for me. We weren’t back together—not officially. We were co-parents. We were survivors. We were figuring it out.

But when we got to the apartment, Isa looked at the stairs—the steep, wooden stairs leading up to her door.

She looked at her legs, weak from atrophy. She looked at the baby.

“I can’t,” she said softly.

“I know.”

I walked around the car. I picked up the car seat with one hand. Then, I bent down and scooped Isa up in the other arm.

She was lighter than she used to be.

“Robert, put me down,” she protested, but she wrapped her arms around my neck.

“Shut up, Isa.”

I carried her up the stairs. My back didn’t complain. I felt strong. Useful.

I kicked the door open. I set her down on the bed. I set Eli in the crib.

The room was exactly as I had left it. The painting of me sleeping was still on the easel.

“Welcome home,” I said.

The first month at home was a blur of sleeplessness and milk.

I moved into the apartment. It just happened. I slept on the floor on a camping mattress for the first week because I was terrified to leave them alone. Then I moved to the couch.

I learned the rhythm of the house.

Isa was still sick. The Lupus was in remission, but “remission” didn’t mean “healthy.” It meant she had good days and bad days. On bad days, her joints swelled, and she couldn’t hold a paintbrush. On those days, I did everything.

I learned to cook. Not the sous-vide scallops I used to order, but real food. Scrambled eggs. Toast. Soup. I burned things. I set off the smoke detector three times. Isa laughed until she cried.

“The great Robert Blackwell,” she teased, watching me scrape burnt eggs off a pan. “Defeated by a non-stick skillet.”

“It’s a defective pan,” I grumbled, feeding Eli a bottle with my other hand.

My phone rang occasionally. The assistant I had kept—a young woman named Sarah who was loyal to a fault—called with updates I didn’t ask for.

“The stock is down 12% since the announcement,” she told me one afternoon while I was folding laundry.

“Only 12%?” I asked, holding up a tiny onesie. “The market is soft.”

“Sir, the board is threatening to sue for breach of fiduciary duty.”

“Let them sue. Send the paperwork to the house. I’ll use it to start the fireplace.”

“Sir… are you… happy?”

I looked across the room. Isa was sitting by the window, sketching Eli. The light caught the curve of her neck. The baby was gurgling, blowing milk bubbles. The room was small, cluttered, and smelled of lavender and spit-up.

“Sarah,” I said. “I’m busy. Call me next month.”

I realized then that I wasn’t just “happy.” Happiness is a spike of dopamine. I was content. I was grounded.

The turning point for us—for Robert and Isa—came on a rainy Tuesday in November.

I was working at the small desk I had squeezed into the corner. I wasn’t running the empire, but I had started consulting for small, local businesses. Helping a bakery manage its cash flow. Helping a boat repair shop negotiate a lease. It was small money, pitiful money by my old standards, but it was honest work.

Isa was standing behind me.

“You’re good at that,” she said.

I turned around. “It’s just numbers.”

“No,” she said. “It’s fixing things. You always liked fixing things. You just used to fix things that didn’t matter.”

She reached out and touched my face. Her hand was cool. The swelling was gone.

“You fixed us,” she whispered.

“I broke us,” I corrected. “I’m just trying to glue the pieces back together.”

She sat on my lap. It was the first time she had touched me affectionately since before the divorce.

“The pieces are better this way,” she said. “We were a vase before, Robert. Perfect, shiny, hollow. Now… now we’re a mosaic. Broken pieces made into something else.”

I wrapped my arms around her. I buried my face in her neck.

“I missed you,” I said. “Even when I was with you in New York, I missed you. I missed this.”

“I missed you too,” she said. “I missed the man you were hiding.”

We kissed. It wasn’t the passionate, movie-star kiss of our wedding day. It was slow. It tasted of tea and exhaustion and hope.

Six months later.

The Oregon coast is not known for its sunshine, but when it shows up, it feels like a miracle.

It was a golden evening. The tide was low.

We went to the beach.

I carried Eli in a carrier strapped to my chest. He was six months old now. Heavy. Solid. He had chubby cheeks and eyes that watched everything with a serious intensity that was entirely mine.

Isa walked beside us. She was wearing a thick sweater and jeans, her hair loose in the wind. She walked with a cane now—sometimes her hips hurt—but she walked with her head high.

We walked down to the water’s edge. The waves crashed and receded, a rhythmic breathing of the earth.

I looked at my wife. I looked at my son.

I thought about the man in the glass tower. That man seemed like a stranger. A sad, lonely stranger who thought he owned the world because he could buy it.

I had lost the tower. I had lost the jet. I had lost the title. My net worth was a fraction of what it used to be. The legal battles were expensive. The medical bills were astronomical.

But standing there, with the salt spray on my face and the weight of my son against my chest, I knew the math.

I looked at Isa.

“Hey,” I said.

She turned, smiling. “Hey.”

“I’m rich,” I said.

She laughed, the sound mingling with the cry of the gulls. “We’re renting an apartment above a bookstore, Robert. And we drive a Toyota.”

“I know,” I said. I reached out and took her hand. “I’m the richest man on earth.”

She squeezed my hand. “Yeah. You are.”

Eli burbled, reaching for the wind.

I watched the sun dip below the horizon, painting the sky in violent purples and soft oranges. I didn’t check my watch. I didn’t check my phone. I didn’t have anywhere else to be.

The deal was closed. The merger was complete.

I was home.

News

Her Elite Boarding School Had A Perfect Reputation, But When The First Student Confessed Her Terrifying Secret, A Century-Old Lie Began To Unravel, Exposing A Horror Hidden Beneath Their Feet.

The words came out as a whisper, so faint I almost missed them in the heavy silence of my new…

She was forced from First Class for ‘not looking the part,’ but when her shirt slipped, the pilot saw the Navy SEAL tattoo on her back… and grounded the plane to confront a ghost from a mission that went terribly wrong.

The woman’s voice was sharp, cutting through the quiet hum of the boarding cabin like shattered glass. — “That’s my…

They cuffed a US General at a gas station, calling her a pretender before she could even show her ID. But the black SUV that screeched in to save her revealed a far deadlier enemy was watching her every move.

The police cruiser swerved in front of my SUV with a hostility that felt personal. At 7:12 a.m., the suburban…

I laughed when the 12-year-old daughter of a fallen sniper demanded to shoot on my SEAL range, but then she broke every record, revealing a secret that put a target on her back—and mine.

The girl who walked onto my base shouldn’t have been there. Twelve years old, maybe, with eyes that held the…

He cuffed the 16-year-old twins for a crime they didn’t commit, but the black SUV pulling up behind his patrol car carried a truth that would make him beg for his career, his freedom, and his future.

The shriek of tires on asphalt was the first sound of their world breaking. One moment, my twin sister Taylor…

My 3-star General’s uniform couldn’t protect me from a racist cop at my own mother’s funeral. He thought he was the law in his small town; he didn’t know that by arresting me, he had just declared war on the Pentagon.

The Alabama air was so heavy with the scent of lilies it felt like a second shroud. I stood on…

End of content

No more pages to load