Part 1

My name is Tyler. For most people, the world is a big, loud, chaotic place. But for me, my world was small. It fit neatly inside the screen of my computer and the four walls of our modest house in Springfield, Missouri.

I’ve always been a little different. The doctors called it high-functioning autism and a seizure disorder. It meant I couldn’t hold down a regular 9-to-5 job or drive a car safely, but it didn’t mean I didn’t feel things. I felt everything. I loved my family deeply. I loved my online friends. I loved posting my random thoughts on Facebook—everything from the weather to my favorite TV shows. It was my way of connecting, of saying, “I am here.”

We were a typical American family on the outside. My mom, Diane, was a nurse. That was a point of comfort for me. Moms are supposed to take care of you, and a nurse mom? That’s like a superhero. She played the organ at our church. My dad, Mark, was a blues musician with a soul full of rhythm and a mind that sometimes raced too fast because of his bipolar disorder. Then there were my three sisters. We were tight-knit. Maybe a little too tight-knit.

The atmosphere in our house shifted in the spring of 2012. It wasn’t a sudden explosion; it was a slow, creeping fog.

It started with Dad. He was the life of the house, always playing his guitar, always talking about his band, “Messing with Destiny.” But he started getting tired. Not just “long day at work” tired, but “can’t lift his head” tired. He was stumbling around the kitchen, slurring his words like he was drunk, but I knew he hadn’t been drinking.

I chronicled it all online. It was my way of processing the fear. “My father is slowly getting sicker,” I typed one afternoon, my fingers trembling slightly over the keyboard. “His voice is slurred. His walking is wobbly.”

I remember watching him try to walk down the hallway. He looked like a puppet with cut strings. I tried to help him, guiding him to his bedroom, but he was dead weight. Mom was there, of course. She was always there, hovering with a glass of Gatorade or a soda. “You need to stay hydrated, Mark,” she’d say. Her voice was calm. Clinical.

I trusted her. Why wouldn’t I? She was the nurse. She knew what was best.

Dad never went to the doctor. He hated hospitals, and Mom didn’t push him. She just kept feeding him those drinks. And then, one Sunday, the music stopped. We came home from church, and Dad was gone. Just like that. The coroner said “natural causes.” A stroke, maybe. Or a heart attack.

We cried. We mourned. But Mom… Mom was weirdly okay. She planned the memorial like she was planning a dinner party. No tears, just logistics. She talked about his life insurance money like it was a lottery win. “We can finally move to a better neighborhood,” she said. And we did. We moved to a nicer house, a fresh start.

I thought the darkness was behind us. I thought Dad’s death was just a tragic accident, a blip in the universe’s plan. I was wrong.

A few months after we settled into the new house, the fog came back. But this time, it was wrapping its cold fingers around me.

It started with a stomach ache. Just a cramp, I told myself. Maybe I ate something bad. But then the vomiting started. Violent, uncontrollable sickness that left me shaking on the bathroom floor. My head felt like it was being squeezed in a vise. My muscles ached so bad I could barely type my status updates.

“I feel like I have the worst flu of my life,” I told my sister, Sarah. She looked at me with wide, scared eyes, but she didn’t say much.

Mom was there again, her shadow looming over my bed. “Here, Tyler,” she said, handing me a glass of cherry cola. “Drink this. It’ll settle your stomach.”

The soda tasted sweet, maybe a little too sweet, almost syrupy. But I drank it. I drank it because I wanted to get better. I wanted to go back to my computer, to my friends, to my life.

“Thanks, Mom,” I whispered, my throat burning.

She smiled, but it didn’t reach her eyes. It was a blank look. “Rest now,” she said.

Days turned into a blur of agony. I stopped posting online. I couldn’t focus on the screen. The pain in my kidneys was unbearable. I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t think. I was just lying there, waiting for the medicine to work, waiting for my nurse mother to save me.

But the medicine wasn’t working. I was getting worse. And the strangest thing was… I saw my sister Rachel whispering with Mom in the kitchen. They stopped talking whenever I tried to crawl out of my room. They looked at me not with concern, but with… annoyance?

One afternoon, the pain was so bad I couldn’t breathe. My chest felt tight. I looked at the empty soda bottle on my nightstand. The same soda Dad used to drink.

A terrifying thought sparked in my foggy brain. It was impossible. It was crazy. But the pieces were fitting together in a way that made my blood run cold.

Dad got sick after drinking Mom’s special drinks. Now I was sick after drinking Mom’s special drinks.

I tried to call out to Sarah, to tell her to run, to tell her not to drink anything. But my voice was gone. The darkness was closing in, heavy and final. And the last thing I saw was Mom standing in the doorway, holding another glass, waiting.

Part 2

The Silent House

When Tyler died, the silence in our house wasn’t peaceful; it was heavy. It felt like a physical weight pressing down on my chest. I was twenty-four years old, a college graduate with a degree in French and History, but in that house, I felt like a helpless child.

We buried Tyler without a funeral. Mom said it was too expensive, that funerals were for the living, not the dead. She cremated him quickly, just like she had with Dad only five months earlier. There was no service, no gathering of friends, no closure. Just an urn and a sudden, terrifying emptiness where my brother used to be.

Mom—Diane—didn’t cry. That was the thing that kept nagging at the back of my mind, a scratch I couldn’t itch. When Dad died, she was efficient. When Tyler died, she was… relieved? I tried to push that thought away. It was a sinful thought. Mom was a nurse. She was a woman of God. She was the rock of this family. She was just strong, I told myself. She had to be strong for us.

But the atmosphere in our new house—the “better” house we bought with Dad’s life insurance money—began to curdle. It wasn’t a home anymore; it was a waiting room.

The Golden Child and The Scapegoat

I spent most of my days in my bedroom. The job market in Springfield was tough, especially for someone with my specific degree, and my student loans were a looming cloud over my head. I applied for jobs, but mostly I escaped into the internet.

My younger sister, Rachel, was Mom’s favorite. Everyone knew it. They were like two peas in a pod, always whispering in the kitchen, sharing inside jokes. Rachel was the “Golden Child”—talented, musical, the one Mom bragged about on Facebook. I was the one Mom sighed about. “Sarah needs to get her life together,” she’d say to neighbors, loud enough for me to hear through the thin walls.

I felt like a burden. And in our house, being a burden was dangerous, though I didn’t realize just how dangerous yet.

The Sickness Returns

It was June 2013, almost a year after Tyler passed. The summer heat in Missouri was stifling, a wet blanket of humidity. I woke up one Tuesday morning feeling off. My head was throbbing, a dull ache behind my eyes that Tylenol couldn’t touch.

By the afternoon, the nausea hit. It wasn’t like a normal stomach bug. It felt like someone had lit a fire inside my gut. I curled up on the bathroom floor, the cold tile pressing against my cheek, waiting for the vomiting to stop. But it didn’t.

“Mom,” I called out, my voice raspy.

She appeared in the doorway. She didn’t rush to my side. She didn’t feel my forehead. She just stood there, looking down at me with that same unreadable expression she had when Tyler was dying.

“You’re just dehydrated, Sarah,” she said, her voice crisp. “It’s this heat. You need fluids.”

She went to the kitchen and came back with a tall glass of Coca-Cola. “Drink this. The sugar will help.”

I was grateful. I took the glass, my hands shaking, and drank it down. It tasted weirdly sweet, almost cloying, but I was so thirsty I didn’t care. I trusted her. She was a nurse. She saved lives for a living.

The Descent

Over the next few days, I fell into a nightmare. The headache turned into a blinding migraine. My muscles felt like they were dissolving. I couldn’t walk in a straight line. I’d try to go to the kitchen and end up stumbling into the wall, my legs refusing to obey my brain.

I remembered watching Dad stumble like that. I remembered Tyler slurring his words. Panic started to rise in my chest, fighting through the fog of pain. Am I dying too? Is it genetic? Is there a curse on the Staudte family?

“Mom, I think I need to go to the hospital,” I pleaded one night. I was lying in bed, soaked in sweat, my heart racing erratically.

Mom sat on the edge of my bed. She stroked my hair, but her touch felt cold. “Sarah, honey, we can’t afford the emergency room for a flu. You know our insurance situation. You just need to rest. Drink your soda. You’ll be fine.”

Rachel came in sometimes. She would stand by the door, watching me. I looked at my sister, my best friend growing up, begging her with my eyes to help me.

“Does it hurt?” Rachel asked once, her voice flat.

“Yes,” I whispered. “It feels like I’m dying.”

Rachel just nodded, turned around, and walked away.

The Collapse

I lost track of time. Days bled into nights. The vomiting was constant. I stopped eating. The only thing I consumed were the drinks Mom brought me. Gatorade. Soda. Juice. Always pre-poured. Always ready.

One morning, I tried to stand up to use the bathroom, and my legs simply gave out. I hit the floor hard. I tried to push myself up, but my arms were like jelly. I couldn’t move. Paralysis was creeping up my limbs.

I laid there on the carpet for what felt like hours. I could hear the TV on in the living room. I could hear Mom laughing on the phone.

She’s laughing, I thought, a tear sliding down my nose. I’m dying in here, and she’s laughing.

Finally, Rachel found me. She didn’t scream. She didn’t cry. She just called out, “Mom, Sarah’s on the floor again.”

They came in and looked at me. I was drifting in and out of consciousness. The pain in my lower back—my kidneys—was excruciating, a sharp, stabbing agony that made me want to scream, but I didn’t have the breath.

“Maybe we should take her in,” Rachel said. Not out of concern, but like she was suggesting we take out the trash because it was starting to smell.

“Fine,” Mom sighed. “Help me get her to the car.”

They dragged me. Literally dragged me. I was dead weight. They shoved me into the backseat of the car. I remember looking up at the sky through the window, thinking it was the last time I would ever see the sun.

The ICU

The hospital was a blur of bright lights and urgent voices. I remember a nurse looking at my vitals and yelling for a doctor.

“She’s crashing! BP is bottoming out!”

I was wheeled into a trauma room. Tubes were shoved down my throat. Needles pierced my arms. I wanted to tell them. I wanted to say, My dad died like this. My brother died like this. But the darkness swallowed me whole.

I fell into a coma. My kidneys had shut down. My liver was failing. My brain was swelling.

While I lay there, fighting a battle I didn’t understand, the doctors were baffled. I was young. I had been healthy. There was no infection, no virus, no genetic marker that could explain why my organs were liquefying inside my body.

But there was one thing the doctors noticed. It wasn’t medical. It was behavioral.

The nurses watched my mother. They saw a woman who didn’t look like a grieving mother. She didn’t pace the halls. She didn’t pray by my bedside. She flirted with the male doctors. She joked with the staff. She talked about a vacation to Florida she was planning.

“My daughter is just a drama queen,” she told a nurse, laughing lightly. “She probably just got into something under the sink.”

That comment—under the sink—was the first thread that, when pulled, would unravel the entire horrific tapestry of our lives.

Part 3

The Anonymous Call

While I was hooked up to life support, trapped in the darkness of a coma, the world outside was beginning to wake up to the horror of the Staudte household.

It wasn’t a detective who started it. It was our Pastor.

He had presided over Dad’s memorial. He had heard about Tyler’s sudden death. And now, hearing that I—the third healthy adult in the house—was at death’s door with the same mysterious symptoms, his spirit was troubled. He couldn’t shake the feeling that this was not bad luck. This was evil.

He called the Springfield Police Department. “I’m a pastor,” he told them, his voice shaking. “And I think… I think someone is killing that family.”

The Interrogation

Detectives began to dig. They pulled Dad’s file. Natural causes. They pulled Tyler’s file. Prior medical issues. Then they looked at my charts. Total organ failure. Acidosis.

They brought Mom in for questioning.

I learned later what happened in that small, windowless room. At first, Mom played the part of the weary, tragic widow. She talked about God. She talked about how hard she worked. But the detectives were smart. They kept pressing. They asked about the life insurance. They asked why she hadn’t called 911 sooner.

“I don’t know,” she kept saying. “I just don’t know.”

But then, the lead detective looked her in the eye and appealed to her faith. He told her that the truth would set her free. He told her that Sarah—me—was fighting for her life, and if she knew anything, she had to say it.

And then, the mask slipped.

Diane Staudte, the church organist, the nurse, the mother, leaned back in her chair and sighed. “I put it in their drinks,” she said, as casually as if she were giving a recipe for apple pie.

“What did you put in their drinks, Diane?”

“Antifreeze.”

The Lethal Sweetener

Antifreeze. Ethylene glycol. It’s odorless. It’s sweet. And it is deadly. In the body, it turns into crystals that shred your kidneys and attack your brain. It is a slow, agonizing way to die.

Mom admitted everything. She said Dad was a “deadbeat.” She said she hated him. She said Tyler was “a burden” because of his autism. She said he was annoying.

And me? Why did she poison me?

“Sarah has student loans,” Mom told the police. “She wouldn’t get a job. I didn’t want to pay her debts anymore.”

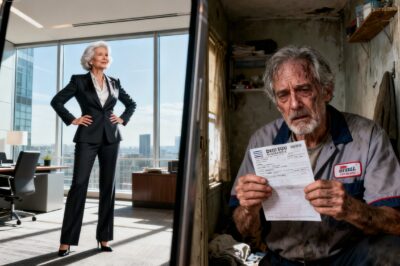

She killed my father because she was bored. She killed my brother because he was needy. And she tried to kill me because I cost too much. We weren’t people to her. We were line items on a budget she wanted to cut.

The Second Betrayal

But the horror wasn’t over. The police suspected Mom couldn’t have done this alone. Tyler was a big guy. I was an adult. How did she keep poisoning us without us noticing?

They brought Rachel in. My little sister. My confidante.

Rachel sat in the interrogation room, looking small and innocent. She denied everything at first. But then, they found her diary.

It was a purple notebook, filled with teenage handwriting. But the words weren’t about crushes or homework.

“It’s sad when I realize how my father will pass on in the next two months and how Shaun will move on shortly after,” she had written in June 2011. “It’ll be tough getting used to the changes but everything will work out.”

She knew. She knew before it happened.

Under pressure, Rachel broke. And her confession was even more chilling than Mom’s.

“Mom would pour the antifreeze in,” Rachel explained, her voice devoid of emotion. “But sometimes I would do it. Dad was taking too long to die, so we upped the dose.”

The detective asked her about me. “Did you want Sarah to die?”

Rachel shrugged. “She’s annoying. She’s nosy. She fights with me.”

My sister. The girl I shared a bathroom with. The girl I defended on the playground. She watched me writhe in pain on the floor. She stepped over my body. She handed me the poisoned Coca-Cola and watched me drink it, knowing it was killing me.

She did it because she wanted her inheritance. She did it because she wanted my room. She did it because Mom told her to.

Waking Up to Hell

I woke up weeks later. The first thing I noticed was that I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t move my legs. My brain felt like it was full of cotton. The antifreeze had caused severe neurological damage.

A detective and a social worker were standing by my bed. They looked pitying. Sad.

“Sarah,” the detective said gently. “We know why you’re sick.”

I tried to ask Why? but only a groan came out.

“Your mother and your sister Rachel have been arrested,” he said. “They poisoned you, Sarah. They poisoned Mark and Tyler too.”

My world shattered. It wasn’t a tragic disease. It wasn’t a curse. It was murder.

I lay there, tears streaming down my face, unable to wipe them away. The people supposed to love me the most—the woman who gave me life and the sister who grew up beside me—had decided I didn’t deserve to exist.

They had watched us die, one by one, over dinner.

Part 4

The Survivor’s Guilt

Recovering from murder is different than recovering from an accident. When you break a leg falling off a bike, the bone heals. When your brain is damaged by poison fed to you by your mother, the healing is… complicated.

I spent months in rehabilitation. I had to relearn how to walk. I had to relearn how to talk without slurring. The antifreeze had left permanent scars on my brain. I have seizures now. I have memory gaps. I am a 26-year-old woman living in the body of someone much older.

But the physical pain was nothing compared to the emotional void.

I was alone. Dad was dead. Tyler was dead. Mom and Rachel were in jail awaiting trial. Our house—the house bought with Dad’s blood money—was a crime scene.

I had to ask myself the question every survivor asks: Why me? Why did I survive when Tyler didn’t?

Maybe it was because I was older. Maybe it was because I had more body mass. Or maybe, God kept me here to tell the truth. To make sure they didn’t get away with it.

The Courtroom

I faced them in court. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

Seeing Mom in an orange jumpsuit was surreal. She looked smaller. Without her makeup, without her nurse’s scrubs, she looked like a stranger. She wouldn’t look me in the eye. She stared at the table, her face hard and cold.

Rachel was different. She looked terrified. She was just a kid, really. A kid who had been groomed by a monster. But then I remembered her diary. I remembered her stepping over me while I vomited. She was a victim of Mom, yes, but she was also a predator.

I sat in my wheelchair and read my victim impact statement. My voice shook, but I forced the words out.

“I prefer to be a survivor than a victim,” I told the court. “You took my father. You took my brother. You tried to take me. You took my health. But you didn’t take my spirit.”

Rachel pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. She agreed to testify against Mom. In her statement, she apologized to me. She said she hated herself. She said she was brainwashed.

Do I believe her? I don’t know. Part of me wants to hug my little sister and tell her it’s okay. The other part of me remembers the taste of that poisoned soda.

Rachel was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole in 42 years. She will be an old woman before she breathes free air again.

Mom… Diane Staudte… she pleaded guilty too, to avoid the death penalty. She was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. She will die in a cage. Just like she trapped us in that house, she is now trapped forever.

Forgiveness and the Future

People ask me how I sleep at night. They ask if I’m angry.

I was angry for a long time. I was furious. I screamed at God. I screamed at the empty walls of my assisted living facility.

But anger is a poison too. It eats you from the inside out, just like the antifreeze. If I stayed angry, if I let the hate consume me, then Mom would win. She would still be controlling my life from behind bars.

So, I chose to forgive.

I didn’t forgive them for them. I forgave them for me. I forgave them so I could cut the cord.

I still have nightmares. Sometimes I dream that Dad and Tyler are standing at the foot of my bed. They don’t say anything; they just watch over me. I like to think they are my guardian angels now.

I’m studying again. I want to be a translator. I want to travel to France, to see the Eiffel Tower, to eat croissants in a café where nobody knows my name, where nobody knows I’m “The Girl Who Survived the Antifreeze Mom.”

The Final Lesson

If you take anything from my story, let it be this: Evil doesn’t always look like a monster in a movie. It doesn’t always hide in the shadows.

Sometimes evil wears a nurse’s uniform. Sometimes it plays the church organ on Sundays. Sometimes it smiles at you and hands you a cold drink on a hot day.

Trust your gut. If something feels wrong, it is. If you feel unsafe, leave. Don’t worry about being polite. Don’t worry about hurting feelings.

I stayed because I wanted to be a good daughter. I almost died for it.

My name is Sarah. I lost my family, but I found myself. And I am still here.

News

He laughed as I moved into a tiny rental while he took a million-dollar payout and his new young bride—until his health failed and his karma came collecting…

Part 1 “I want a divorce.” Those were the three words it took to completely shatter 41 years of unwavering…

When My Children Whispered “Let Her Suffer” for Inheritance Money, I Engineered the Perfect R*venge

Part 1: The Disappearing Lifeline P*in is supposed to break you. Mine was about to break them instead. My name…

A single mother of two inherits a massive Charleston estate overnight from a patient she barely knew, sparking a brutal family war that exposes a web of deep resentment and leaves a grieving family wondering who the real victim is…

Part 1 It was a bitter February morning in Charleston, South Carolina, when everything changed. I had been in the…

“Message not delivered” became a multi-million dollar mistake for three entitled siblings—who is the stranger taking their inheritance?

Part 1 They say blood is thicker than water, but nobody tells you what happens when that blood turns cold…

My Children Abandoned Me For 10 Years, So I Secretly Sold Our Estate, Took Millions, And Vanished Without A Trace…

Part 1 I stood in my immaculate, eerily quiet kitchen on Thanksgiving morning, staring at the perfectly roasted, 20-pound turkey…

My Three Wealthy Children Blocked My Number When I Was Diagnosed With A Terminal Illness—So I Left My Entire $600,000 Estate To The Young Delivery Boy Who Held My Hand During Chemo And Watched My Kids Lose Their Minds In Court.

Part 1 The doctor’s words still echo in my mind like a d*ath sentence. “Stage three aggressive, Mrs. Vance. We…

End of content

No more pages to load